Lehman formula: Difference between revisions

(The LinkTitles extension automatically added links to existing pages (<a target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener" class="external free" href="https://github.com/bovender/LinkTitles">https://github.com/bovender/LinkTitles</a>).) |

m (Text cleaning) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Lehman formula''' is also known as the Lehman scale and it defines the rate of compensation that a bank or a finder should receive for brokering services. The formula was initially used by [[investment]] banks, individual or corporate finders to raise the capital for a business. It was applied in public offerings or private placements. The commission was paid by the vendor of the business once the funds have been cleared. The Lehman scale is used with the amounts greater than one million dollars. Below one million dollars mark, investment banks and brokers offered set fees (A. R. Lajoux, J. F.Weston 1999) | |||

'''Lehman formula''' is also known as the Lehman scale and it defines the rate of compensation that a bank or a finder should receive for brokering services. The formula was initially used by [[investment]] banks, individual or corporate finders to raise the capital for a business. It was applied in public offerings or private placements. The commission was paid by the vendor of the business once the funds have been cleared. The Lehman scale is used with the amounts greater than one million dollars. Below one million dollars mark, investment banks and brokers offered set fees | |||

==The original version of the Lehman Scale== | ==The original version of the Lehman Scale== | ||

| Line 26: | Line 9: | ||

* 1% of the purchase price thereafter | * 1% of the purchase price thereafter | ||

The above scale was commonly used in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s; usually when a large stock investment transaction was made with an investment bank or institutional broker as well as for private asset transactions. However, it has stopped to be the [[standard]] due to [[inflation]]. In 1990s some banks developed different variants of the formula by replacing 1 million to 10 million dollars, 4% of the next 10 million dollars etc., which was considered to be extremely greedy. Nowadays, the formula is only used under few circumstances, mostly by individuals, not companies, who declare the relationship, however they do not have any other role in the execution of the deal, like distribution, legal, analytics or administrative | The above scale was commonly used in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s; usually when a large stock investment transaction was made with an investment bank or institutional broker as well as for private asset transactions. However, it has stopped to be the [[standard]] due to [[inflation]]. In 1990s some banks developed different variants of the formula by replacing 1 million to 10 million dollars, 4% of the next 10 million dollars etc., which was considered to be extremely greedy. Nowadays, the formula is only used under few circumstances, mostly by individuals, not companies, who declare the relationship, however they do not have any other role in the execution of the deal, like distribution, legal, analytics or administrative (R. De Haas & N. Van Horen 2012, p. 231-237) | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

Lehman Brothers was a global financial services [[firm]] that in the early 1970s developed the formula with the commissions applied for underwriting and capital raising. Before the scale was introduced, the rate varied from institution to institution, in some cases reaching even more than 15%. The formula was applied to the dollars as a [[total capital]] of a transaction, rather than a larger share of equity dollars | Lehman Brothers was a global financial services [[firm]] that in the early 1970s developed the formula with the commissions applied for underwriting and capital raising. Before the scale was introduced, the rate varied from institution to institution, in some cases reaching even more than 15%. The formula was applied to the dollars as a [[total capital]] of a transaction, rather than a larger share of equity dollars (A. S. Kaplan 1985) | ||

In September 2008, Lehman Brothers announced the bankruptcy which was the result of exodus of most of their clients, massive losses in their stock and due to [[devaluation]] of assets by credit [[rating agencies]]. This bankruptcy was the largest in the US history and it had a huge impact on the late 2000s [[global financial crisis]]; global markets immediately plummeted | In September 2008, Lehman Brothers announced the bankruptcy which was the result of exodus of most of their clients, massive losses in their stock and due to [[devaluation]] of assets by credit [[rating agencies]]. This bankruptcy was the largest in the US history and it had a huge impact on the late 2000s [[global financial crisis]]; global markets immediately plummeted (M. Williams 2010). | ||

The report from 2010, which was examined by the court, proved that Lehman executives were using cosmetic accounting tricks so that at the end of each quarter their finances looked less unstable than they really were. This practice was described by Lehman as the outright sale of securities and created "a materially misleading picture of the firm’s financial condition in late 2007 and | The report from 2010, which was examined by the court, proved that Lehman executives were using cosmetic accounting tricks so that at the end of each quarter their finances looked less unstable than they really were. This practice was described by Lehman as the outright sale of securities and created "a materially misleading picture of the firm’s financial condition in late 2007 and 2008". (M.Trumbull 2010). | ||

==Formula variations== | ==Formula variations== | ||

Current commissions vary, some banks seek higher rates (even Triple Lehman) while other push for lower rates, for example in case of $100 million and higher transactions. It is also a common practice to run transactions in-house. Such example was the Google IPO, they performed the analytics, execution and structure requirements while a Dutch [[Auction]] was used for pricing and banks were used for [[distribution network]]. Retainers and ongoing fees are typical for big transactions. Usually underwriters try to get the [[company]] that is collecting the capital dedicated to pay the underwriter's legal fees which are significant | Current commissions vary, some banks seek higher rates (even Triple Lehman) while other push for lower rates, for example in case of $100 million and higher transactions. It is also a common practice to run transactions in-house. Such example was the Google IPO, they performed the analytics, execution and structure requirements while a Dutch [[Auction]] was used for pricing and banks were used for [[distribution network]]. Retainers and ongoing fees are typical for big transactions. Usually underwriters try to get the [[company]] that is collecting the capital dedicated to pay the underwriter's legal fees which are significant (A. R. Lajoux, J. F. Weston 1999) | ||

==Examples of Lehman formula== | ==Examples of Lehman formula== | ||

| Line 65: | Line 48: | ||

In summary, the Lehman formula is the traditional approach to establishing the rate of compensation for a finder or a broker, but there are several other approaches that can be used to set the appropriate fee for services. These include a flat fee, a percentage fee, and a contingent fee. | In summary, the Lehman formula is the traditional approach to establishing the rate of compensation for a finder or a broker, but there are several other approaches that can be used to set the appropriate fee for services. These include a flat fee, a percentage fee, and a contingent fee. | ||

{{infobox5|list1={{i5link|a=[[Commercial rate]]}} — {{i5link|a=[[Placement fee]]}} — {{i5link|a=[[Depreciation vs. amortization]]}} — {{i5link|a=[[Residual payment]]}} — {{i5link|a=[[Staged payments]]}} — {{i5link|a=[[Collateral management]]}} — {{i5link|a=[[Fictitious asset]]}} — {{i5link|a=[[Brokered deposit]]}} — {{i5link|a=[[Forced sale value]]}} }} | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 70: | Line 55: | ||

* Kaplan A. S. (1985) [http://www.unitecllc.com/epub/download/id=976901&type=file ''Lehman Brothers: 1850-1984: a chronicle'']. New York: Lehman Brothers | * Kaplan A. S. (1985) [http://www.unitecllc.com/epub/download/id=976901&type=file ''Lehman Brothers: 1850-1984: a chronicle'']. New York: Lehman Brothers | ||

* Lajoux A. R. Weston J. F. (1999) ''The art of M&A [[financing]] and [[refinancing]]: a guide to sources and instruments for external growth''. McGraw-Hill Professional, New York, London. | * Lajoux A. R. Weston J. F. (1999) ''The art of M&A [[financing]] and [[refinancing]]: a guide to sources and instruments for external growth''. McGraw-Hill Professional, New York, London. | ||

* Trumbull M. (2010). ''Lehman Bros. used accounting trick amid financial crisis | * Trumbull M. (2010). ''Lehman Bros. used accounting trick amid financial crisis - and earlier''. The Christian Science Monitor. | ||

* United States Congress U.S. (2002) [https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-107shrg78622/pdf/CHRG-107shrg78622.pdf | * United States Congress U.S. (2002) [https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-107shrg78622/pdf/CHRG-107shrg78622.pdf ''The Watchdogs Didn't Bark: Enron and the Wall Street analysts''.] | ||

* Williams M. (2010). ''Uncontrolled [[Risk]]''. McGraw-Hill [[Education]]. | * Williams M. (2010). ''Uncontrolled [[Risk]]''. McGraw-Hill [[Education]]. | ||

[[Category:Financial management]] | [[Category:Financial management]] | ||

{{a|Katarzyna Mamak}} | {{a|Katarzyna Mamak}} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:47, 17 November 2023

Lehman formula is also known as the Lehman scale and it defines the rate of compensation that a bank or a finder should receive for brokering services. The formula was initially used by investment banks, individual or corporate finders to raise the capital for a business. It was applied in public offerings or private placements. The commission was paid by the vendor of the business once the funds have been cleared. The Lehman scale is used with the amounts greater than one million dollars. Below one million dollars mark, investment banks and brokers offered set fees (A. R. Lajoux, J. F.Weston 1999)

The original version of the Lehman Scale

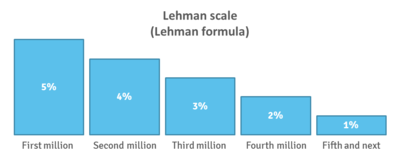

- 5% applied to the first million of purchase price

- 4% of the second million of purchase price

- 3% of the third million of purchase price

- 2% of the fourth million purchase price

- 1% of the purchase price thereafter

The above scale was commonly used in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s; usually when a large stock investment transaction was made with an investment bank or institutional broker as well as for private asset transactions. However, it has stopped to be the standard due to inflation. In 1990s some banks developed different variants of the formula by replacing 1 million to 10 million dollars, 4% of the next 10 million dollars etc., which was considered to be extremely greedy. Nowadays, the formula is only used under few circumstances, mostly by individuals, not companies, who declare the relationship, however they do not have any other role in the execution of the deal, like distribution, legal, analytics or administrative (R. De Haas & N. Van Horen 2012, p. 231-237)

History

Lehman Brothers was a global financial services firm that in the early 1970s developed the formula with the commissions applied for underwriting and capital raising. Before the scale was introduced, the rate varied from institution to institution, in some cases reaching even more than 15%. The formula was applied to the dollars as a total capital of a transaction, rather than a larger share of equity dollars (A. S. Kaplan 1985)

In September 2008, Lehman Brothers announced the bankruptcy which was the result of exodus of most of their clients, massive losses in their stock and due to devaluation of assets by credit rating agencies. This bankruptcy was the largest in the US history and it had a huge impact on the late 2000s global financial crisis; global markets immediately plummeted (M. Williams 2010).

The report from 2010, which was examined by the court, proved that Lehman executives were using cosmetic accounting tricks so that at the end of each quarter their finances looked less unstable than they really were. This practice was described by Lehman as the outright sale of securities and created "a materially misleading picture of the firm’s financial condition in late 2007 and 2008". (M.Trumbull 2010).

Formula variations

Current commissions vary, some banks seek higher rates (even Triple Lehman) while other push for lower rates, for example in case of $100 million and higher transactions. It is also a common practice to run transactions in-house. Such example was the Google IPO, they performed the analytics, execution and structure requirements while a Dutch Auction was used for pricing and banks were used for distribution network. Retainers and ongoing fees are typical for big transactions. Usually underwriters try to get the company that is collecting the capital dedicated to pay the underwriter's legal fees which are significant (A. R. Lajoux, J. F. Weston 1999)

Examples of Lehman formula

- Example 1: The Lehman formula is used by investment banks and brokers who are providing brokering services to raise funds for a business. For example, if a business needs $100 million in capital, a broker or an investment bank will negotiate a commission with the vendor based on the Lehman scale. The commission will be calculated based on the amount raised, with the rate of compensation ranging from 1% to 5%.

- Example 2: The Lehman formula is also used in private placements. For example, if a company needs to raise $10 million from a private investor, the broker or investment bank will negotiate a commission with the investor based on the Lehman scale. The commission will be calculated based on the amount raised, with the rate of compensation ranging from 1% to 5%.

- Example 3: The Lehman formula is also used in public offerings. For example, if a company needs to raise $100 million through a public offering, the broker or investment bank will negotiate a commission with the investor based on the Lehman scale. The commission will be calculated based on the amount raised, with the rate of compensation ranging from 1% to 5%.

Advantages of Lehman formula

The Lehman formula has several advantages, including:

- It allows for a fair and transparent rate of compensation for the services of an investment bank or a finder. Since the formula is based on the amount of funds raised, it incentivizes the broker to work hard to ensure that the maximum amount of capital is raised for the business.

- The formula is also beneficial for the vendor of the business, since it offers a degree of certainty in terms of the fee structure. The vendor is able to accurately anticipate the cost of the services, which helps in budgeting and planning.

- The Lehman formula also offers flexibility, since it allows for customization of the fee structure with respect to the amount of capital raised. This can be useful for businesses that require a large amount of capital, since the fee structure can be tailored to their individual needs.

Limitations of Lehman formula

The Lehman formula has certain limitations:

- It only applies to transactions worth more than one million dollars, so it cannot be used to broker transactions of smaller amounts.

- The formula is not applicable in certain transactions, such as private placements which require a more detailed negotiation.

- The formula does not take into account the complexity of the transaction and the time spent on the deal, so it cannot be used to accurately calculate the commission.

- The formula does not consider the value of the services provided by the broker, so it cannot be used to determine the value of the commission.

- The formula does not provide an accurate picture of the market, as it does not account for different types of investments or market conditions.

- The formula does not take into account the costs associated with the transaction, such as legal fees and other expenses.

The Lehman formula is the traditional approach to establishing the rate of compensation of a finder or a broker for services rendered. However, there are several other approaches that can be used to determine the appropriate fee for services. These include:

- Flat Fee: A flat fee is a predetermined amount that is paid regardless of the size of the transaction. This approach is often used when the services provided are of a limited nature, such as providing access to a certain market segment.

- Percentage Fee: A percentage fee is charged as a percentage of the transaction amount. This approach is generally used when the services provided are of a more complex nature, such as facilitating a complex transaction.

- Contingent Fee: A contingent fee is based on a predetermined outcome, such as the completion of a transaction. This approach is typically used when the services provided are of a more specialized nature, such as providing advice about the transaction.

In summary, the Lehman formula is the traditional approach to establishing the rate of compensation for a finder or a broker, but there are several other approaches that can be used to set the appropriate fee for services. These include a flat fee, a percentage fee, and a contingent fee.

| Lehman formula — recommended articles |

| Commercial rate — Placement fee — Depreciation vs. amortization — Residual payment — Staged payments — Collateral management — Fictitious asset — Brokered deposit — Forced sale value |

References

- De Haas, R., & Van Horen, N. (2012). International shock transmission after the Lehman Brothers collapse: Evidence from syndicated lending. American Economic Review, 102(3), 231-37.

- Kaplan A. S. (1985) Lehman Brothers: 1850-1984: a chronicle. New York: Lehman Brothers

- Lajoux A. R. Weston J. F. (1999) The art of M&A financing and refinancing: a guide to sources and instruments for external growth. McGraw-Hill Professional, New York, London.

- Trumbull M. (2010). Lehman Bros. used accounting trick amid financial crisis - and earlier. The Christian Science Monitor.

- United States Congress U.S. (2002) The Watchdogs Didn't Bark: Enron and the Wall Street analysts.

- Williams M. (2010). Uncontrolled Risk. McGraw-Hill Education.

Author: Katarzyna Mamak